History of scurvy, why does it matter today?

Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.

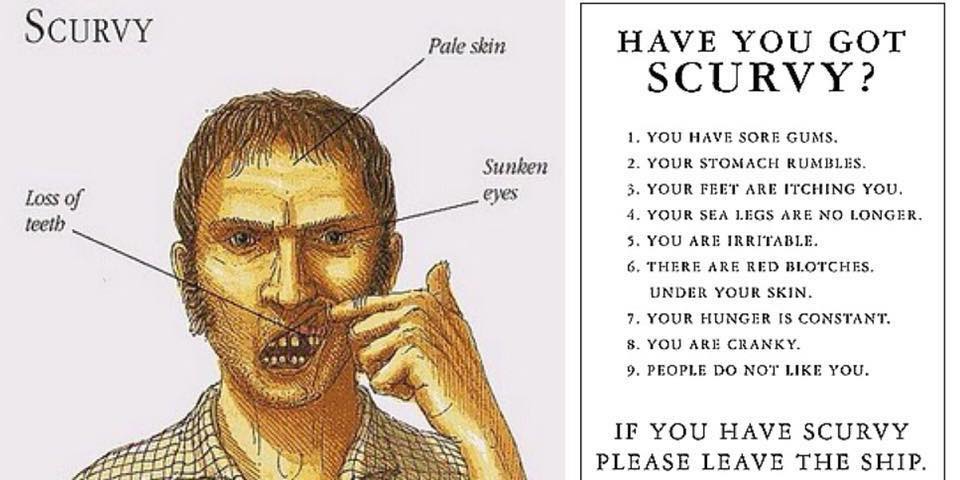

The history of scurvy is a stark warning, for those who insist in a pathogen cause for disease in the face of contradictory evidence. Scurvy is a terrible disease. The body, deficient in vitamin C is no longer able to make proper connective tissues. Late symptoms of scurvy include:

- Bleeding gums that swell and turn purple

- Teeth become loose or fall out

- Skin easily bruises and bleeds

- The opening up of previously healed wounds and scars

- Bleeding into joints and muscles

- Death

For hundreds of years scurvy was especially common among sailors, who spent month away at sea eating no fresh fruits or vegetables. Robbed of the vitamin C found in such foods, their bodies where literally unable to form the connective tissue that holds us together.

The cause and cure was discovered over and over again. Each time this information that would have easily saved thousands from a terrible death was discarded because it was not what people wished to believe.

Sir Richard Hawkins

In 1593 the crew of British ship led by Sir Richard Hawkins discovered that eating oranges and lemons in Brazil cured the condition. Regardless, Hawkins stayed with the current wisdom of the time in believing the scurvy was caused by unsanitary conditions on the ship. Thus what could have been the discovery that ended scurvy once and fall became a footnote in history.

Francois Pyrard

About the same time French negotiator Francois Pyrard wrote a detailed account of long voyage to South East Asia. Aside from being held 5 years captives by locals, his crew also suffered scurvy. According to his account the severe nutritional deficiency was "very contagious even by approaching or breathing another's breath." His crew did experience reversal of scurvy by eating citrus fruit. This discovery was once again discarded because everyone knew it was caused by unclean conditions on ships.

James Lind publishes the cure for scurvy

In 1734 the captain of a British ship marooned a sailor with a particularly bad case of scurvy on an island. As everyone knew, scurvy was contagious and the captain didn't want other members of the crew to catch it. Eating food available on the island the sailor recovered. He later found passage back to England on another ship.

This prompted navy surgeon James Lind to investigate a possible cure for scurvy. Lind concluded that some nutritional factor found in citrus fruits, lacking from the diet over long journey, was the cause of scurvy. He published this in a book in 1753. This information was ignored.

James Cook

In 1769 the English captain James Cook discovered, one again independently, that fresh vegetable and citrus fruits worked as a treatment for scurvy. Regardless, he insisted that good hygiene and fresh air was essential as well. The significance of his discovery was thus missed, because he did not leave the contagious disease paradigm.

Limey

In 1795 the British navy began adding lime or lemon juice into sailors diets. This is the origin of the slang work for sailors, Limey. At this point the debate over the cause and treatment of scury should have ended. For hundreds of years it was treated as a contagious disease. This prevented nothing. In multiple instances the disease was prevented and treated with fresh fruits. Yet this was not enough. At bacteria were discovered, and with that the germ theory of disease, once again scurvy was called a contagious disease.

Jean-Antoine Villemin

Jean-Antoinie Villemin was a member of the Paris Academy of medicine. His great discovery was that tuberculosis is an infectious disease. This led him to become a passionate germ hunter and thus he turned his work to scurvy. A paraphrased excerpt from his writing:

Scurvy is a contagious miasm, comparable to typhus, which occurs in epidemic form when people are closely congregated in large groups as in prisons, naval vessels and siege's... We have many examples of well-fed sailor and soldiers going down with scurvy, while others less well fed do not. Also, we have positive evidence of the spread of the disease by contagion - for example, the introduction of scurvy in to French military hospitals by veterans returning from the Crimea, and the rapid spread of scurvy from one sailor to another in naval vessels.

A key point is that just because there is a disease clusters, that does not mean it must be contagious. All there needs to be is a common factor among people in the cluster causing the disease. In this case, it was a diet absent of fresh fruits and vegetable's.

Frederick Jackson and the Ptomaines theory of scurvy

Odd are you probably never heard about ptoamaines. It was theorized that bacteria poisoned meat, producing the "ptomaines," which then caused scurvy. In 1899 the Royakl Society of London funded research in which monkeys where fed rotten meat. When the monkeys got this, that only inspired the bacteria hunters to search for the bacterial cause of scurvy.

1898 - The American Pediatric Association on scurvy

The search for scurvy causing bacteria continues

The germ theory of disease and discovery of actual germs that could be proved to cause illness created a craze of bacteria hunters. Experiments continued, searching for the scurvy bacteria in patients. Transplanting bacteria found in one animal with scurvy into another. This research led to no scurvy breakthrough, but it did have real world consequences. In WW1 doctors blamed scurvy in soldiers on bacteria and unsanitary conditions. Soliders at Gallipoli in 1915 developed scurvy from poor food rations.

Finally, vitamin C is purified

It was not until the purification of vitamin C and research into its function that the bacteria hunters search for the scurvy pathogen ended. The reason why the search for the cause of scurvy took so long was summarized chemistry professor of the University of Edinburgh, C.P. Stewart in 1953:

One factor which undoubtedly held up the development of the concept of deficiency diseases was the discovery of bacteria in the nineteenth century and the consequent preoccupation of scientists and doctors with positive infective agents in disease. So strong was the impetus provided by bacteriology that many diseases which we now know to be due to nutritional or endocrine deficiencies where, as late as 1910, thought to be "toxemias." In default of any evidence of an active infecting microorganism they were ascribed to the remote effects of imaginary toxins elaborated by bacteria.

Over 300 years until acceptance

It took over 300 years from Richard Hawkins 1593 discovery, until the 1930's for medicine to accept that scurvy is caused by a nutritional deficiency. Although scientists may not have yet had the technology to isolate vitamin C, the empirical evidence that a diet lacking in fresh fruits or vegetables caused scurvy was obvious. It was the belief that some infectious agent had to be the cause, which kept scurvy going long after it could have been eliminated.

All this would be nothing more than historical footnote, except similar processes continues to go on today. At first scurvy was a "miasma." As science evolved it became a bacterial infection. Then it became toxemia caused by bacteria. If the viral theory of disease, along with virus hunters existed back then, they undoubtedly would have been chasing it down. Searching scurvy patients for any incidental virus found to blame it on.

Note on research for this article

This article is mostly a summary from Peter Duesberg's book, Inventing The Aids Virus. Published in 1996. This book is if anything, even more relevant today than when first published, in understanding the history of virology and how that field functions.